Personalised Learning, Connectivism & Affordance

Personalised learning seems all the rage at the moment, one of the edtech trends for 2018 apparently. Much as I like the idea, though, it does give me the jitters a little. It's not just because people don't seem to be able to agree on exactly what it is, or the fact that it may be just at the wrong point on the hype cycle, there's something deeper that I've not been able to put my finger on. Until now.

What the theory of Connectivism proposes is that learning actually resides not in the objects on the map, but in the connections that are made between those objects. What we learn is how objects relate to each other, how they connect to each other, whether that is a connection between two objects in the world, between us and an object in the world, or even in the connection between two concepts that we've already discovered. The map isn't what's learnt, connections are what's learnt.

As soon as we're born, we start to make connections between objects: hard floor, soft flesh, chewy toys, etc. ... and everything from then on is all connected to those very first experiences. We're just an amazing connector machine!

The affordance of anything in the world depends on you, and what you're doing in the world at any one moment in time. Take the pair of shoes in the example above. The usual affordance of a pair of shoes is to protect your feet, but if there's a scorpion in your room first thing in the morning (and it's happened to me!) what those shoes "provide or furnish" is the ability to destroy a threat without getting damaged. The "transaction possibilities" are different depending on circumstance, on your individual need. Treating affordance as deterministic, i.e. as if something always has the same affordance no matter what the situation, is a common misconception.

The link here with personalised learning is twofold:

I feel we need to find ways to bring more of the learner back into the process, and let them shape their own learning; stop treating learners like something that education is done to, instead develop systems that can flex according to their needs. I suspect the dream of education by technology is going to be too much for computers for some time yet, but maybe that's not such a bad thing. After all, surely that's what teachers are for. We shouldn't keep pretending that edtech can transform learning, much better to see it as a catalyst for well developed pedagogic approaches.

The problem with Personalised Learning

It was a post that's been repeated a couple of times in different spaces that got me thinking (thanks to Stephen Downes for the initial link), which originated in EdWeek. It quotes Larry Berger, CEO of Amplify, in his "confession" about personalized learning:"Until a few years ago, I was a great believer in what might be called the 'engineering' model of personalized learning, which is still what most people mean by personalized learning. The model works as follows:

- You start with a map of all the things that kids need to learn.

- Then you measure the kids so that you can place each kid on the map in just the spot where they know everything behind them, and in front of them is what they should learn next.

- Then you assemble a vast library of learning objects and ask an algorithm to sort through it to find the optimal learning object for each kid at that particular moment.

- Then you make each kid use the learning object.

- Then you measure the kids again. If they have learned what you wanted them to learn, you move them to the next place on the map. If they didn't learn it, you try something simpler.

If the map, the assessments, and the library were used by millions of kids, then the algorithms would get smarter and smarter, and make better, more personalized choices about which things to put in front of which kids.

I spent a decade believing in this model—the map, the measure, and the library, all powered by big data algorithms.

Here's the problem: The map doesn't exist, the measurement is impossible, and we have, collectively, built only 5% of the library. So we need to move beyond this engineering model. Once we do, we find that many more compelling and more realistic frontiers of personalized learning opening up."As an educational researcher, and a specialist in digital technologies, I must admit it was a little heartened to read this 'confession'. Like many, I too feel the lure of a technological solution to the challenges of teaching and learning, but at the same time consider this mechanical model of education way out of touch with what we know about how learning takes place. Which brings me on to the subject of Connectivism.

The power of Connectivism

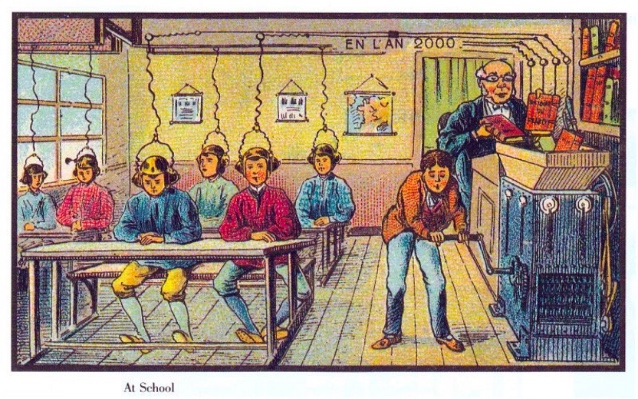

What I think is wrong from the "map & measure" model that Larry discusses above, apart from his own observations about the lack of the map, the challenges of measuring, etc., is where the learning actually is. What he is proposing is, of course, a model of teaching and learning where all the information that is required to be known by students simply needs to be transmitted into their heads. It's basically a transmission model of education, but with clever computers rather than teachers. Kind of like this famous image from the 1900s, that tried to predict learning in the year 2000:As soon as we're born, we start to make connections between objects: hard floor, soft flesh, chewy toys, etc. ... and everything from then on is all connected to those very first experiences. We're just an amazing connector machine!

The role of Affordance

So where does affordance fit into all this? Affordance, to quote James Gibson, is what something "provides or furnishes". For example, a knife provides the ability to cut something, a cup provides the ability to hold a liquid, a pair of shoes provides the ability to protect feet from damage. I define it in my doctoral thesis as the "transaction possibilities" provided by objects around us, i.e. what you get back from interacting with objects, be they animate or inanimate. But, crucially, it is a relational concept.The affordance of anything in the world depends on you, and what you're doing in the world at any one moment in time. Take the pair of shoes in the example above. The usual affordance of a pair of shoes is to protect your feet, but if there's a scorpion in your room first thing in the morning (and it's happened to me!) what those shoes "provide or furnish" is the ability to destroy a threat without getting damaged. The "transaction possibilities" are different depending on circumstance, on your individual need. Treating affordance as deterministic, i.e. as if something always has the same affordance no matter what the situation, is a common misconception.

The link here with personalised learning is twofold:

- The theory of Connectivism suggests that any computer-based system that tries to help children learn through the kind of adaptive learning systems that are so popular today needs to build into its algorithms the ability to link between broader concepts. It's not enough to build isolated silos of knowledge about topics; even if you are (unwittingly, perhaps) scaffolding connections in those narrow silos; broader understanding comes from connections between topics - and that means cross-discipline as well as within your subject.

- The theory of Affordance suggests that personal choice is critical. Simply telling a child what they need to learn based on a computer decision completely ignores the state of the individual at that moment in time. Some children will grasp more 'complex' concepts before the (supposedly) easier ones, some may do well on a subject one day and badly the next, some might use knowledge from an experience in a totally different setting to inform the present one. Learning is inherently personal; I'd argue what we actually learn is the affordance of objects in the world, but as those affordances are relative to us then they cannot be simply transmitted. They need to be discovered (constructed) in relation to our existing set of connections.

I feel we need to find ways to bring more of the learner back into the process, and let them shape their own learning; stop treating learners like something that education is done to, instead develop systems that can flex according to their needs. I suspect the dream of education by technology is going to be too much for computers for some time yet, but maybe that's not such a bad thing. After all, surely that's what teachers are for. We shouldn't keep pretending that edtech can transform learning, much better to see it as a catalyst for well developed pedagogic approaches.

Comments

Post a Comment